Diggers 2023 | Blackgrounds | ROMANIZATION

5 stunning archaeological discoveries that may finally be unearthed in 2023

Predicting the future is tricky, but based on our research, we've made some educated guesses as to the archaeological discoveries and stories we may see in 2023. There's a possibility that the mummy of Nefertiti will be discovered, as archaeologists are conducting DNA tests in an Egyptian tomb to see if one of the mummies is the remains of the ancient Egyptian queen. We also may learn more about an underground city that flourished in Turkey about 2,000 years ago.

Here are our five archaeological predictions for 2023.

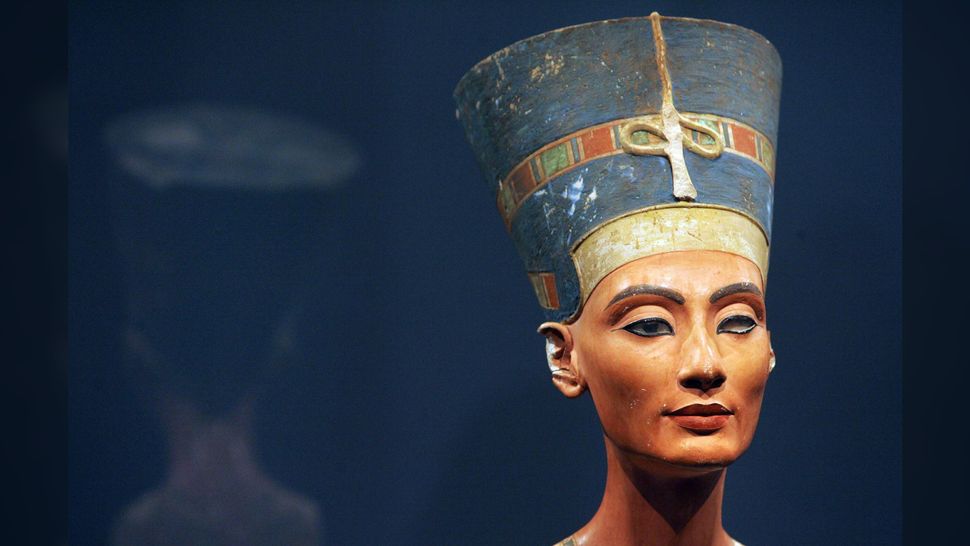

1. Nefertiti's mummy?

A view of the bust of one of history's great beauties, Queen Nefertiti of Egypt. (Image credit: OLIVER LANG / Staff via Getty Images)

First found in modern times in 1817, the tomb "KV 21," as Egyptologists call it, is located in the Valley of the Kings and contains two female mummies, according to the Theban Mapping Project (opens in new tab). At present, a team led by Zahi Hawass, former Egyptian minister of antiquities, is re-examining the tomb and its mummies by conducting DNA tests. Hawass told Live Science that the team is examining the possibility that one of the mummies is Nefertiti. While it's uncertain whether scientists will find the remains of the ancient Egyptian queen, there is a good chance we will hear more about this tomb and the mummies buried within it in 2023.

2. Underground city in Turkey

In 2022, archaeologists in Midyat, Turkey, discovered an underground city that dates back 2,000 years and may have been home to up to 70,000 people. The remains of a Christian church and Jewish synagogue have been found, and it's possible that people in the underground city were trying to hide from the Roman Empire, which ruled the area and at times persecuted Christians and Jews.

One important detail is that only 5% of the city has been excavated so far. Research is ongoing, so it's possible that new discoveries will be made in this underground city in 2023.

3. Repatriated artifacts, possibly even the Elgin Marbles

A set of Benin Bronzes at the National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C. (Image credit: Amanda Andrade-Rhoades/For The Washington Post via Getty Images)

(LONG OVERDUE) Museums around the world are going through a reckoning; some institutions are accessing their collections and deciding whether certain artifacts should be returned to their culture or country of origin. (LOOTING?) For instance, intricate metal sculptures known as the Benin Bronzes were looted from the kingdom of Benin (present-day southwest Nigeria) when the British attacked in 1897. Many of those bronzes are now in museums around Europe, the United States and New Zealand, according to The Art Newspaper (opens in new tab). However, Germany returned 21 of the Benin Bronzes to Nigeria in December 2022, The Guardian reported (opens in new tab), and the University of Cambridge in the U.K. announced in December that it would return 116 of its Benin Bronzes to Nigeria, the BBC reported.

In another case, the National Museum of Scotland plans to repatriate a looted totem pole to the Nisga'a Nation of British Columbia, Canada, The Art Newspaper reported (opens in new tab).

In addition, there are talks underway for the British Museum to return the Parthenon Marbles, also known as the Elgin Marbles, to Greece. British law stipulates that the British Museum cannot transfer ownership of its artifacts, but a workaround could be to share the marbles with Greece while putting on a new show of Greek artifacts in the marbles' place.

4. Ukraine's heritage LOOTED

The ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine has resulted in the theft, damage and destruction of numerous heritage structures and artifacts. As of Dec. 12, UNESCO has verified damage to 227 heritage sites, including museums, religious buildings and libraries. There has also been extensive looting. For instance, Russian authorities looted gold Scythian artifacts from a museum in Russian-occupied Melitopol.

Over the past few months, Ukraine's military has been retaking territory and even liberated Kherson, a major city that had been occupied by Russia. As Ukraine retakes more territory, we will likely hear more about damaged, stolen and looted artifacts and archaeological sites. It's also possible that some of the artifacts stolen by Russian soldiers will appear for sale online.

5. New ancient finds along the U.K.'s new railway

For the past few years, archaeologists in the United Kingdom have found remarkable artifacts dating to Roman Britain and Anglo-Saxon England as they survey land ahead of construction of High Speed 2 (HS2), a high-speed railway line that will run from London to the West Midlands. This year alone, archaeologists have discovered several ancient sites, including the well-preserved remains of an Iron Age village that transformed into a bustling ancient Roman town in South Northamptonshire, England; a burial ground for rich pagans dating to around the time of the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain in the fifth century A.D.; and an "exquisite" wooden figurine dating to early Roman Britain.

Phase one of the HS2 project is expected to open between 2029 and 2033, so there's still plenty of time to uncover ancient treasures.

👇UK is old MINOAN/ROMAN

Blackgrounds: Ruins of bustling Roman town discovered in UK

Archaeologists have uncovered the exceptionally well-preserved remains of an Iron Age village that grew into a bustling ancient Roman trading town — an archaeological gem with more than 300 Roman coins, glass vessels and water wells — in what is now the district of South Northamptonshire, England in the United Kingdom.

The ancient hotspot — known as Blackgrounds for its black soil — has an abundance of ancient artifacts and structures spanning different time periods, including depictions of deities and Roman game pieces, according to about 80 archaeologists from the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) Headland Infrastructure, who spent the past year excavating the site ahead of the construction of HS2, a new high speed railway.

"What you would see is a whole hive of activity, people doing different things — people living, people working and people trading as well," James West, MOLA site manager, said in a video. (Hive is a word The Minoan use)

Archaeologists have known about Blackgrounds' history since the 18th century, but it wasn't until the HS2 survey and excavation that they realized the site's remarkable preservation. For instance, archaeologists learned that during the Iron Age, the village had more than 30 roundhouses sitting near a road. Over time, the settlement became more prosperous and expanded. During the Roman period, for instance, Blackgrounds people built new stone buildings and roads, according to a statement.

The transition from Iron Age village to Roman town happened so quickly, it's likely that Blackgrounds' inhabitants stayed the same, adapting to the Roman Empire's ways — a transition known as Romanization. This included using Roman customs, products and building techniques, the archaeologists said.

One of these building techniques is a 33-foot-wide (10 meters) Roman road, which is "exceptional in its size," according to the statement, as most Roman roads were no more than 13 feet (4 m) wide, West said. Such a vast road would have been filled with animals and people loading and unloading goods from carts. This road, as well as the nearby River Cherwell, likely helped make Blackgrounds a thriving trade hub.

The excavation revealed that the settlement was divided into different sections, including a domestic sector filled with building foundations, and an industrial park that had workshops, kilns and preserved wells. One part of Blackgrounds had fiery red dirt, an indication that burning had happened at the site — for example for bread baking, foundries for metal work or a kiln for pottery.

Other artifacts indicative of Blackgrounds' prosperity include Roman weaving accessories, decorative pottery and a Roman snake head-shaped brooch. The archaeology team even found galena, a lead sulfide mineral that ancient Romans crushed and mixed with oil to concoct makeup.

The team also unearthed a set of shackles that are similar to those found in Great Casterton, a village in England's East Midlands region, Live Science previously reported. While the newfound shackles were not discovered with a human burial, their presence suggests that Blackgrounds had either slave labor or criminal activity, according to the statement.

The archaeologists are now mapping out the Blackgrounds settlement; specialists at MOLA Headland Infrastructure are also cleaning and examining the artifacts found at the site.

Originally published on Live Science.

Comments

Post a Comment

leave a message please